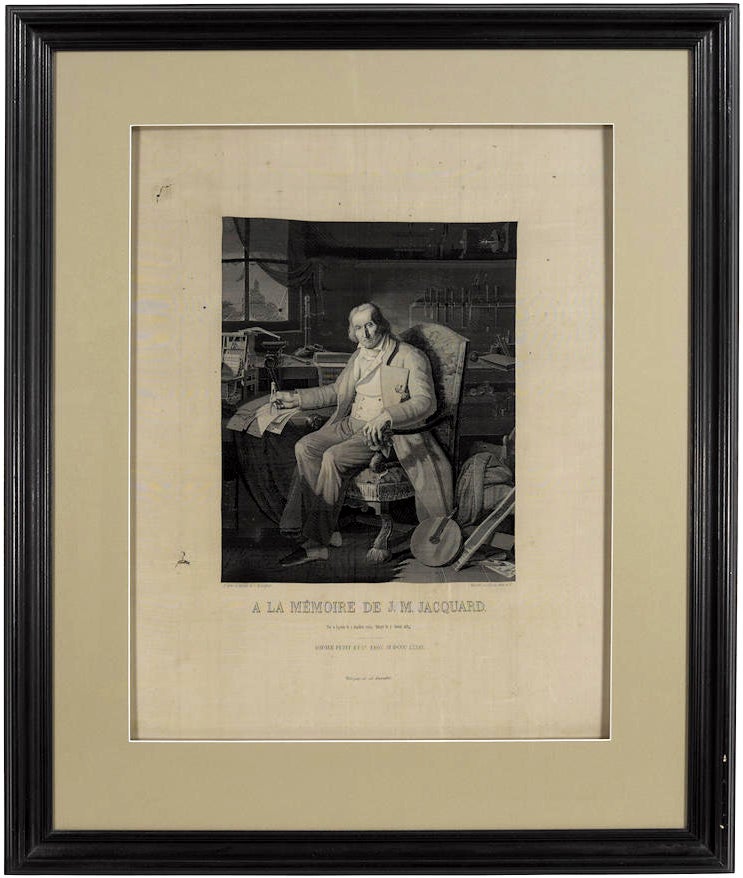

Portrait manufactured by Didier, Petit et Cie, woven in silk.

Publisher Information: 1839.

Jacquard, Joseph Marie (1752-1834). Portrait in silk of Joseph-Marie Jacquard after an original oil portrait by Claude Bonnefond, manufactured by Didier, Petit et Cie; woven by Michel-Marie Carquillat (1803–1884) in Lyon, France, 1839. The image, including caption and Carquillat’s name, taking credit for the weaving, is 55 x 34 cm.; the full piece of silk including blank margins is 85 x 66 cm. The visible portion of the image in the frame is 72 x 54.5 cm., and the frame measures 104 x 84 cm. Minor wear from folding barely visible in the image, but with the image in clear, unfaded and fresh condition. The weaving was professionally treated by a textile conservator, whose conservator’s report and images of before and after are available. Minor flaws visible in the large outer margins of the silk, not affecting the image. In a large and attractive archival frame.

This famous image, of which only a very few examples are known, was woven by machine using 24,000 Jacquard cards, each of which had over 1000 hole positions. The process of mis en carte, or converting the image details to punched cards for the Jacquard mechanism, for this exceptionally large and detailed image, would have taken several workers many months, as the woven image convincingly portrays superfine elements such as a translucent curtain over glass window panes. Once all the “programming” was completed, the process of weaving the image with its 24,000 punched cards would have taken more than eight hours, assuming that the weaver was working at the usual Jacquard loom speed of about forty-eight picks per minute, or about 2800 per hour. More than once this woven image was mistaken for an engraved image. The image was produced only to order, most likely in a small number of examples. Recorded examples are those at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Science Museum, London, The Art Institute of Chicago, and the Computer History Museum, Mountain View, California, Musée de Tissus, Lyons.

The image is the subject of the book by James Essinger entitled Jacquard’s Web: How a Hand Loom Led to the Birth of the Information Age (2004). To Charles Babbage the incredible sophistication of the information processing involved in the mis en carte—what we call programming—of this exceptionally elaborate and beautiful image confirmed the potential of using punched cards for the inputting, programming, and outputting and storage of information in his design and conception of the first general-purpose programmable computer--the Analytical Engine. The highly aesthetic result also confirmed to Babbage that machines were capable of amazingly complex and subtle processes—processes which might eventually emulate the subtlety of the human mind.

“In June 1836 Babbage opted for punched cards to control the machine [the Analytical Engine]. The principle was openly borrowed from the Jacquard loom, which used a string of punched cards to automatically control the pattern of a weave. In the loom, rods were linked to wire hooks, each of which could lift one of the longitudinal threads strung between the frame. The rods were gathered in a rectangular bundle, and the cards were pressed one at a time against the rod ends. If a hole coincided with a rod, the rod passed through the card and no action was taken. If no hole was present then the card pressed back the rod to activate a hook which lifted the associated thread, allowing the shuttle which carried the cross-thread to pass underneath. The cards were strung together with wire, ribbon or tape hinges, and fan-folded into large stacks to form long sequences. The looms were often massive and the loom operator sat inside the frame, sequencing through the cards one at a time by means of a foot pedal or hand lever. The arrangement of holes on the cards determined the pattern of the weave.

“As well as patterned textiles for ordinary use, the technique was used to produce elaborate and complex images as exhibition pieces. One well-known piece was a shaded portrait of Jacquard seated at table with a small model of his loom. The portrait was woven in fine silk by a firm in Lyon using a Jacquard punched-card loom. The image took 24,000 cards to produce, and each card had over 1,000 hole positions. Babbage was much taken with the portrait, which is so fine that it is difficult to tell with the naked eye that it is woven rather than engraved. He hung his own copy of the prized portrait in his drawing room and used it to explain his use of the punched cards in his Engine.

The delicate shading, crafted shadows and fine resolution of the Jacquard portrait challenged existing notions that machines were incapable of subtlety. Gradations of shading were surely a matter of artistic taste rather than the province of machinery, and the portrait blurred the clear lines between industrial production and the arts. Just as the completed section of the Difference Engine played its role in reconciling science and religion through Babbage’s theory of miracles, the portrait played its part in inviting acceptance for the products of industry in a culture in which aesthetics was regarded as the rightful domain of manual craft and art” (Swade, The Cogwheel Brain. Charles Babbage and the Quest to Build the First Computer [2000] 107-8).

Book Id: 46174Price: $17,500.00